The knowledgeable object and the objective of knowledge

Teaching With Objects, a new UMAC publication

Gina Hammond, Andrew Simpson, Eve Guerry & Jane Thogersen

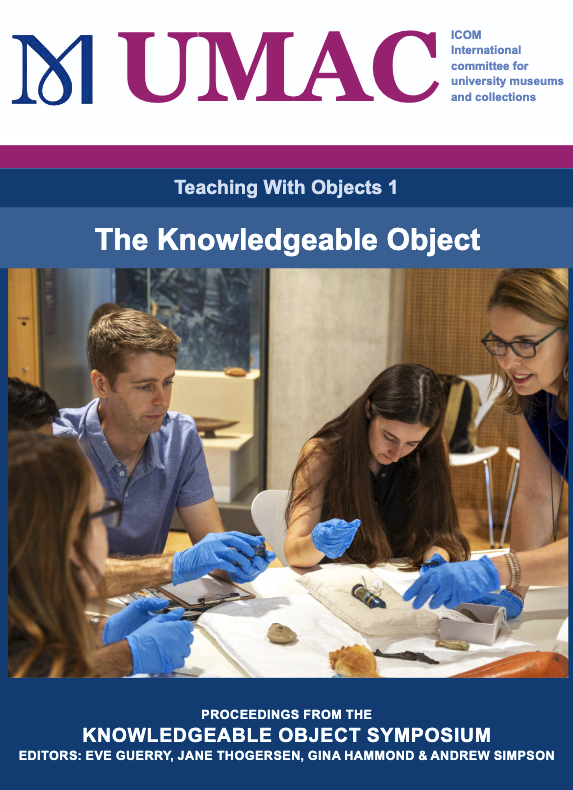

Introducing TWO (1), a new publication from UMAC. Access to the full issue is provided at the end of this article.

The idea that knowledge might be embedded in objects can be traced back to a range of philosophical, cognitive, and even technological viewpoints. The German philosopher Martin Heidegger believed objects are not just passive entities; they carry meaning and function through their relationship with humans (Harman 2002). This suggests that objects carry knowledge not in any explicit sense but because of their designed purpose and context. They are embedded with a form of human understanding and cultural meaning.

In education, the philosopher John Dewey spoke about people’s interaction with objects as being transactional; there was an exchange of sorts between objects and people every time one encountered the other. This was part of Dewey’s foundational education philosophy built around active engagement, constructivism and social interaction (Dewey 1986).

The same idea arises in material culture theory and anthropology; objects can carry knowledge about the culture and history of the people who made them and used them. Cultural specificity and its applications links objects directly with a whole range of intangible factors and criteria. Ancient objects can carry a form of ancient knowledge depending on purpose and application. Things have agency (Brown 2001).

In the modern world, the dramatic new digital extensions and dimensions have opened up new ontologies allowing us to engage with a range of objects that enact new physical and metaphysical modalities. Artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things represent new epistemic digital analogue frameworks with data and information being reshaped in ways that are reshaping our societies (Yarlagadda 2018).

A few years ago, we deployed an eager group of museum studies students in a little experiment (Simpson & Hammond 2012). One group engaged with a selection of objects from two of our campus museums. Another group engaged with images of the same objects. A basic series of questions regarding the objects their form and functions were asked of both groups. Some six months down the track we tested each of the groups for their didactic recall of their engagement with either object or image. Not surprisingly those that engaged with the objects recalled what the objects represented much more effectively than those who simply looked at images of the objects.

A few years later, to enliven the pedagogic utility of university museum collections we explored object-based learning further in a project working with higher education teachers that looked at mapping the curriculum through individual subject units with individual objects in university museum collections (Thogersen et al 2018). The aim was to unlock the resources buried in the university’s museums and maximise their value to teaching staff and curriculum developers. That project sparked new neural connections between collections and courses across campus, and in doing so enlivened the pedagogic possibilities and potential of the institution.

Part of that project involved testing the temperature of object-based learning outside the boundaries of our own campus. The Knowledgeable Object two-day workshop and symposium explored what makes objects so valuable in education and museum contexts. The first day of the seminar induced a thunderous storm and torrential downpour as physical accompanying fanfare about the power of objects. There was a total of 35 presentations on multiple object perspectives from poetry to practicalities all the way through to empathy and engagement. All of them provided unique insights into the pedagogic power of objects.

Some five years later and the Knowledgeable Object has moved to a new campus. The building of the Chau Chak Wing Museum at the University of Sydney brought together a range of discipline specific collections together into the one museum. Part of the rationale behind centralising collections was the potential it would bring in releasing those objects from their traditional disciplinary containment and allow them to become cross-disciplinary vehicles of educational engagement at the University.

Despite the traditional disciplinary structure of teaching and research in higher education, university museum collections are increasingly being seen as tools for facilitating cross-disciplinary engagements. In teaching, object-based learning is a key driver (Simpson 2022). Through the Academic Engagement unit at the Chau Chak Wing Museum areas of the university that had never previously used objects in their teaching programs are now drawing on the museum’s collections to enrich pedagogy (Thogersen & Guerry 2024). The building of new networks across campus via object-based learning at the museum was recognised with the UMAC Award in 2023. This annual award honours excellence and innovation in university museums and collections work. In 2023 the impact of OBL at CCWM was lauded.

So now, some five years after the inaugural Knowledgeable Object meeting, the second Knowledgeable Object symposium was convened, this time at the Chau Chak Wing Museum. The presentations made at the symposium are captured in the series of professional papers herein. What we experienced on the day and what we have attempted to document here is the engaged set of conversations around the application of object-based learning across a diverse range of different professional settings and contexts. These papers represent the growing body of professional practice around objects as practitioners seek out not just new opportunities but also new applications, digital, analogue and hybrid, for our collections. While these conversations are based on a local geographic area, perhaps it is possible that in another five years, the community of practice will be a global one?

UMAC news release, 23rd September 2023

References

BROWN, B. 2001. Thing Theory. Critical Inquiry 28 (1), 1-22.

DEWEY, J. 1986. Experience and education. The educational forum, 50 (3), 241-252, <DOI:10.1080/00131728609335764>.

HARMAN, G. 2002. Tool-Being: Heidegger and the Metaphysics of Objects. Open Court: Chicago & La Salle.

SIMPSON, A. 2022. The Museums and Collections of Higher Education. Routledge: London.

SIMPSON, A. & HAMMOND, G. 2012. University collections and object-based pedagogies. University Museums and Collections Journal 5, 75-81.

THOGERSEN, J. & GUERRY, E. 2024. Academic Connections Across Disciplines: The Museum as Instigator. In King, B. (ed.) New Directions for University Museums, Rowman & Littlefield: New York & London.123-137.

THOGERSEN, J., SIMPSON, A., HAMMOND, G., JANISZEWSKI, L., & GUERRY, E. 2018. Creating curriculum connections: a university museum object-based learning project. Education for Information, 34 (2), 113-120. <https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180190>

YARLAGADDA, R. T. 2018. Internet of Things & Artificial Intelligence in Modern Society. International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts 6 (2), 374-381

Gina Hammond

Australia

Faculty of Medicine, Health and Human Sciences (FMHHS), Macquarie University

Andrew Simpson

Australia

Chau Chak Wing Museum, The University of Sydney