We should fear the fear of damaging objects

When conservation protocols are causing risk

Fresco Sam-Sin

22 April, 2024

Fear in heritage institutes gives birth to one-size-fits-all protocols (e.g. "always wear gloves") of handling objects. But didn't we believe that every object - just like us humans - is its own unique self? One size does not fit all, and so it is the protocols that are putting objects at risk. In the following I would like to question the protocols, and therewith refocus the attention to the needs of the object, and that of the students as well.

Over the years, I have taught countless students the value of spending quality time with objects. My message to them is always the same: the more we look at an object, the more it will tell. Whenever I can, I will bring my own collection of objects to the classroom and workshops. Most of them are of little economic value, while some belong in a museum, insured. When teaching, I learnt to enjoy the moments where I can see students build up their confidence in their handling of the objects, not knowing what their value is. However, it does make me nervous sometimes.

Helen Wang taught me this lesson, which she herself learned from numismatist Joe Cribbs. "Look at the coins!".

Ignorance as the blessing in disguise

I was teaching a workshop at a Dutch highschool. At the beginning I handed the front row an imperial chest, asking them to pass it along. The chest once belonged to a khan of the early Qing empire (ca. 1650). He used it to send off frightening messages to his subordinates within his realm. Having been touched by the khan, this chest is worth serious money. I did not mention its history, nor its value. The students passed the chest around carelessly, all handling it with confidence. By the end of the second row someone in the back even opened the chest and smelled it. He hated the odor. As the chest made its way to the front again, the chest's lid followed as a separate part, as did the little box that sat inside of the chest.

Only when the chest, or the parts thereof, arrived in the last row, I revealed the story behind the chest, together with its value. Clearly, the students that were yet to touch the objects, became nervous. Encouraging them to touch it without fear, some cramped when holding the box, others were clasping the lid, while others trembled when passing it to their peers. I asked myself then and there, when was the object more safe? Before or after hearing about the truth?

Protocol as a risk

When handling objects that are not ours, we tend to be more careful handling them. We want to keep them whole. This feeling is all the more eminent when we find ourselves in a heritage setting. After all, we all are ingrained with the idea that museum collections are inherently precious and valuable. Hence, whenever we are granted the opportunity to touch heritage objects, we get a bit anxious. The feeling is reinforced by a staff that will inform you about the rules and risks of handling "their" objects. After this they will probably follow your every movement. All of it is protocol, and part of it is risky.

Imagine the Special Collections at Leiden University Libraries. It is a place where a lot of my teaching took place. The librarians inform you about what you can and cannot do with an object, what you can and cannot bring to the table. Besides, they will point towards the appropriate safety pillows and paper weights. However, no gloves are needed. Indeed, many special collection libraries agree: wearing gloves will increase the risk of damaging the paper. It is the senses of our fingers that are the best safety measure that we have. Our touch will warn us when the book or manuscript is struggling. So the protocol being introduced, you now find a spot to look at the works that you ordered.

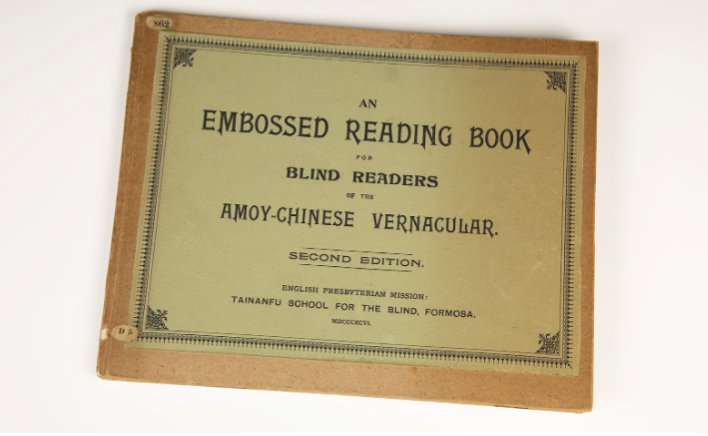

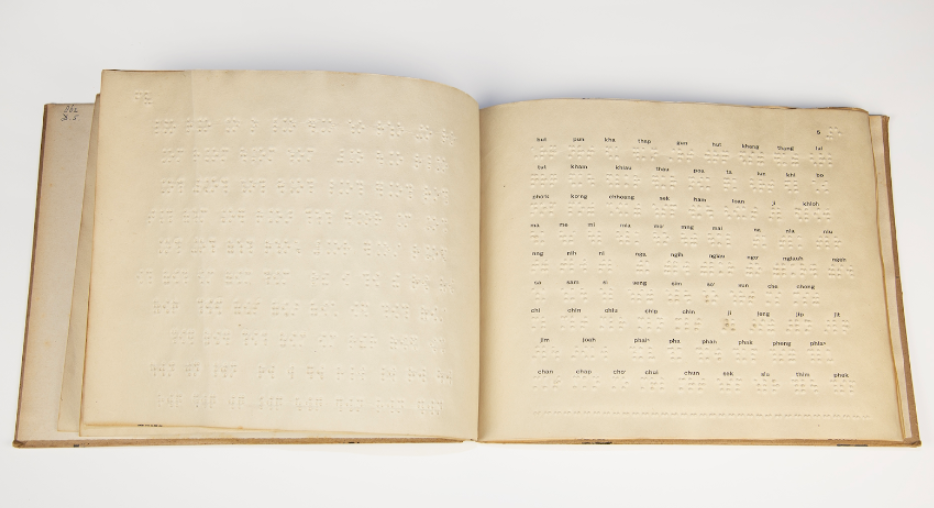

One time I ordered nineteenth century tactile publications from Qing China. Tactile text has my professional and personal interest. I myself am visually impaired and am trained to read Braille. I picked up the books, took a cushion, a paper weight, and walked to a table. I started to look through the books. Turning the pages randomly, allowing myself to get a first overall impression. After that I wanted to read the texts more closely. This would require two actions that would not alarm the librarian, but would, in fact, put the objects at great risk.

Brailliant and over the Moon on Leiden Special Collection blog.

Firstly, when you want to have a book lying open, without having to hold the pages down with your fingers, then the library requires you to put paper weights on top of the paper. But, with tactile texts such as the Moon type, the text is embossed, meaning that the text will rise above the paper. Putting a paper weight on top of this, could potentially cause the raised embossed text to be pushed back into the paper. For people with healthy vision this would not make it illegible, since you can still see the form of the embossment, but for people who rely on the embossment to read, this would make the text illegible.

Adding to the above: embossed text is meant to be read by people who cannot read printed text. Then, when I wanted to read these very rare books, I needed to use my fingertips to feel (and thus read) the text. As all readers of tactile text know, embossed text has an expiration date to it. Depending on the sensitivity in a reader's fingers, the amount of pressure that they will put on the embossments will vary. It is, however, a given that the text will become illegible relatively fast, which is all the more true when tactically reading the embossing on this fragile paper.

The protocol at the Special Collections did not foresee the risks of visitors handling tactile publications. However, should the staff be encouraged to use their own judgment, then surely they will see the same risks that I saw. In other words, the protocol should guide us, but leave room to make decisions based on individual objects.

Learning from the caring hands of collectors

Curators are oftentimes responsible for a very vast collection that will exceed their field of expertise. It is one of the reasons why I find it crucial that museums make an effort to develop a relationship with specialist private collectors and antique dealers. For example, Peter Dekker is an antique dealer with an in-depth knowledge of Asian arms and armor. His knowledge in many cases exceeds the knowledge of museum curators. He and I share a great passion for Manchu history (1616-1912). We are always keen on visiting collections that hold Manchu objects, me and him together, or me together with my students. Our experiences combined reveal some deep rooted problems that have to do with inflexible protocols, as well as the lack of time for a curator to really care for the collection.

Once, Peter Dekker did a thorough search of the Wereldmuseum catalog. Many objects that were labeled as Mongolian and Japanese, were in fact Manchu. He listed all of the wrong information, handed it over to the museum, but no amendments were made to the catalog. It is, when we zoom out, disrespectful to people of Manchu origin that, as is a worldwide phenomenon today, are seeking to connect to their history. But, so far for this side note; let us turn to the materiality (although the bow below also received the outdated label of 'Tartar').

An extreme example of the distance that a curator can have to the collection, Peter Dekker laid bare in his review of the Wereldmuseum Mughal arms.

In the Wereldmuseum collection, Peter Dekker located a breathtaking imperial Manchu bow from the end of the 18th or beginning of the 19th century. A rare find, seeing that this type of Manchu bows is very sensitive to the elements, and therefore only a few are seen today. It is customary at the Wereldmuseum, as it is in the majority of museums nowadays, that, when handling the object, one is required to use latex gloves. Protocol. And, again it is this protocol that will put this bow at risk.

Latex gloves have the risk of getting stuck on uneven surfaces. As we know many objects have uneven surfaces, be it by design or by wear and tear. When a glove gets stuck, then a fragile object such as this bow can become damaged quite easily. Peter Dekker would never use gloves when handling his own antique collection, of which most pieces carry more economic value than the pieces in the Wereldmuseum. Not because he does not care about his objects; on the contrary; it is the fear of damaging an object that makes him avoid the wearing of gloves.

Ivory tower

We are afraid, and it is harming our objects. Did you know that ivory wants to be touched by us? The oils from our skin help to preserve the material. It is, again, a wonderful example to underscore how important it is to see objects as unique beings. The whole educational system is catering more and more towards the needs of the individual. Why not translate this to objects? It seems old fashioned to uphold protocols when they are clearly going against the needs of individual objects. It really can take on Kafkaesk forms.

Once I taught a class about the Qing coin collection at Wereldmuseum. The rarest coins will tremendously decrease in value with even the tiniest scratch on its surface. It is the reason why collectors will never touch coins with gloves, for the fear of sharp fibers and the fear of getting stuck behind corroded details. You pick a coin up by its rim with your thumb and index finger, and hold it there while you inspect it. The museums have decided that gloves have to be worn to touch the coins. I listened, but I felt so very disrespectful towards the coins. And, also, I felt that by adhering to the protocol I was miseducating my students. The ordeal became Kafkaesk when I realized that the majority of the coins were, in fact, recent fakes. Why did I not speak up for the objects?

This video touches upon the no-go of handling coins with gloves.

In conclusion

Objects have many stories to tell, but they need us to give them their voice. Objects also have needs in order for them to survive. Again, they rely on us to be vocal about those needs, especially when their safety is threatened by protocols from the ivory tower. Remember: Ivory wants to be manipulated.