Teaching botany in times of coronavirus at the Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg

Maria Will

18 October, 2024

Germany, Oldenburg

Until recently, botanical studies required being at university, dissecting and observing real flowers under the magnifying glass. Yet the 2020 lockdown due to the coronavirus pandemic imposed whole new conditions. Can you teach botanical skills online? If so, which formats are suited?

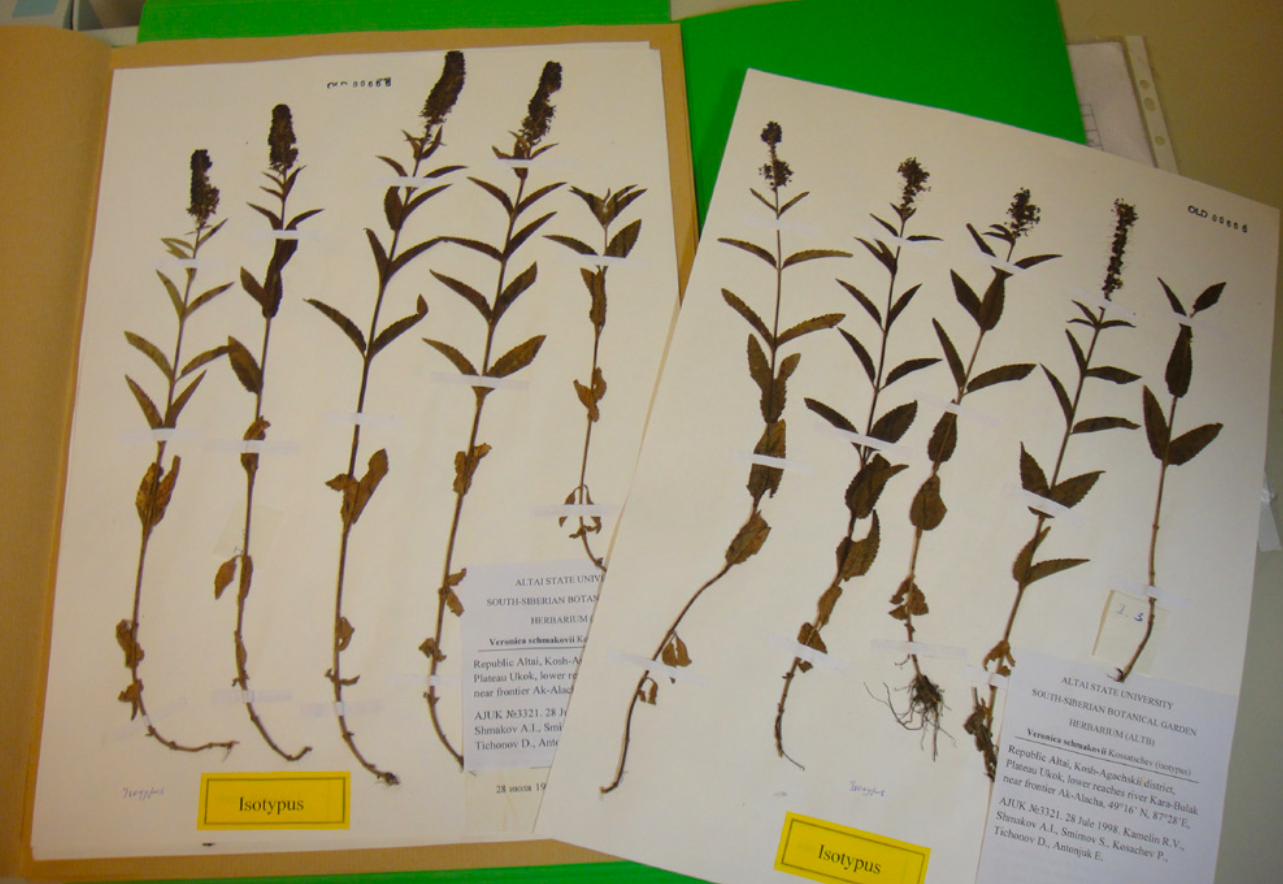

Type specimens from the herbarium of the CvO University of Oldenburg – The genus Veronica (speedwell) is the subject of current research by the Biodiversity and Evolution of Plants working group © Maria Will

What are botany students learning?

Students train to recognise morphological characteristics of plant species through botanical identification exercises. Through literature on plant identification, they acquire a special vocabulary and learn to handle the “plant” object, (historical) didactic models or educational charts, among others. The Botanical Garden, which is also the oldest living collection at Carl von Ossietzky University (CvO), plays a central role (cf. Janiesch 1991 / 2020).

The collection at the Institute of Biology and Environmental Sciences

The repertoire of objects used in the courses is large. It ranges from histological section series, glass slides, herbaria (see Fig. 1), didactic models, prepared animals, animal skeletons and bones, educational boards and wood samples to living plants from the cultivation of the Botanical Garden (see Fig. 2). Selected objects are also used in exhibitions (see Fig. 3), public lectures and guided tours in the Botanic Garden, as well as for teaching samples in schools where students are interning, or in courses of medicine and health sciences.

Beyond their use for Botanical Studies, the objects have also been used in the frame of the certificate programme “Custodial Practice in University Collections” since the academic year 2017/18 (see Krämer in this publication).

Plant identification goes online: how a virus changed teaching methods…

Botanical identification tutorials are compulsory for biology students at the CvO University. They consist of fourteen courses over the whole semester, enriched with two excursions: one to the botanical garden and one, for example, to a forest. All activities offering direct engagement with plants had to be transferred to a digital format in the Summer Semester 2020. This was implemented with the help of an online learning and communication platform, StudIP, and the tools it provides for weekly meetings and for processing tasks within a “Courseware”, synchronously or asynchronously. A digital examination system (VIPS) allowed students to receive feedback, even outside of the meetings.

Various materials and work assignments were integrated into the Courseware and a new virtual chapter of the course was activated every week. Theoretical content was integrated in the form of PDFs, links to tutorials or self-produced videos. For the identification section, a total of 50 plant species were photographed on site and morphological features relevant for their identification were documented (see Fig. 4). When required, photos of details such as pubescence or histological sections were added to the section.

Teaching how to teach biology

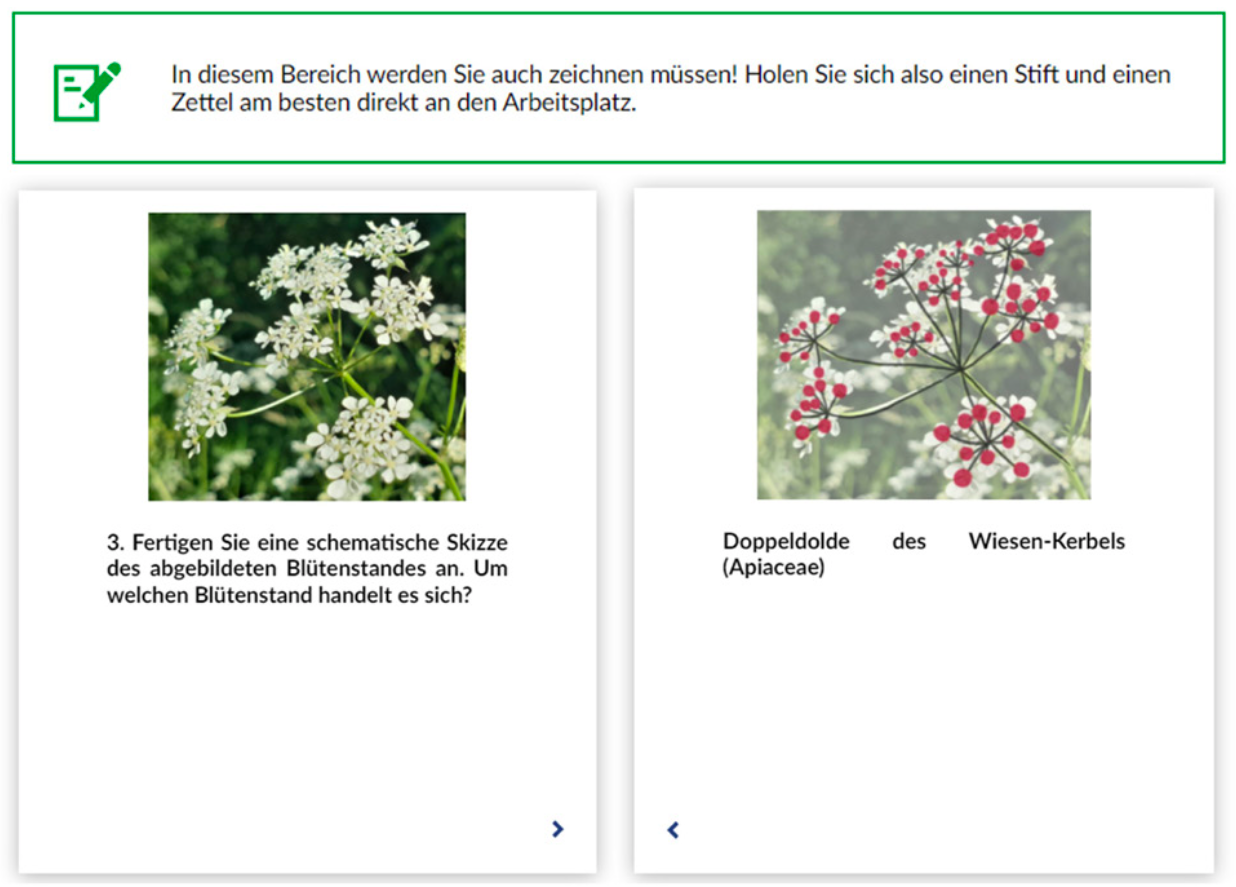

Since the majority of biology students in Oldenburg are teachers in training, parts of the didactic collections were also digitised for the online course. The future teachers will only use such objects in their classrooms if they have used them beforehand. This is why the platform was enhanced with educational charts, flower models of species and plant families and, when necessary, questions about the depicted object.

Access to suitable materials

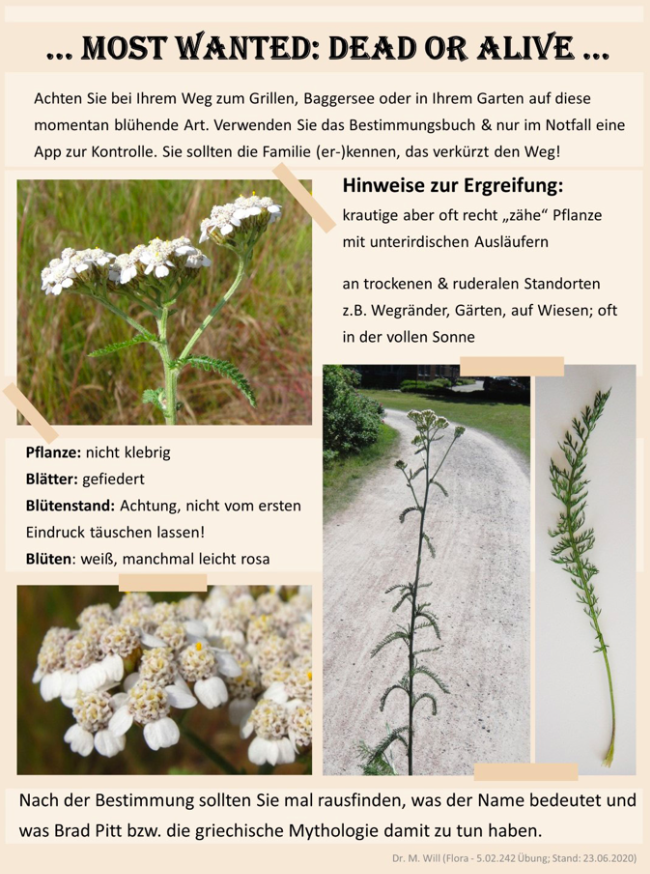

Students at the CvO University have free access to the specialised literature (cf. Jäger / Müller / Ritz et al. 2020) in the form of ebooks. However, for didactic reasons we encourage them to work with an analogue book. In order to compensate for the absence of excursions, students were given several assignments for independent practical work in the field (see Fig. 5). Plant identification apps (cf. Doyen 2020, cf. Doyen / Will in Vb.) were recommended to ensure adequate support and motivate students to actively engage with plant identification.

Digital flashcard on the topic of inflorescences. The latter are covered in the course, but are not particularly popular due to the extensive terminology, among other things. Student teacher Lisa Knittel prepared the topic and presented learning strategies such as drawing to familiarise herself with the objects © modified after Knittel (2020)

Work assignment for searching for and identifying the characteristic and widespread species Achillea millefolium L. (common yarrow) from the Asteraceae family © Maria Will

Forms of exercises

In addition to the identification of a total of 50 species, optional in-depth exercises were offered for nearly all of the plant portraits. The latter covered various formats offered by VIPS / Courseware in order to be as appealing and varied as possible for the students. The following types of questions and tasks were used:

Single choice questions;

Multiple choice questions;

Cloze tests, for learning specific technical terms, e.g. when labelling inflorescences or the structure of a drupe (see Fig. 6);

Interactive flashcards containing a drawing task and showing the solution when turned over (see Fig. 7);

Information and assignments designed to encourage further study and discussion of primary literature or historical sources, e.g. by referring to early findings on flower and pollination biology.

In addition, in-depth tasks were an opportunity for knowledge transfer and a link to the everyday life – e.g. useful plants, ornamental plants, botany in social media, etc. (see Fig. 8). Three B.A. students, who supervised the course as tutors, designed short chapters to accompany these in-depth tasks. These thematic excursions touched on different themes, in order to direct students towards exciting topics for their final theses or study projects. They also featured didactic materials which were the output of the tutors’ bachelor's theses, allowing knowledge to be passed from student to student (see Fig. 6, 7).

3D versus 2D: Lessons from a “forced” switch to digital teaching

Many fears regarding the switch to a digital format have proven irrelevant. After minor adjustments to the online platform, which were made in the summer semester 2021 at the request of students, we now have an optimised version of the Courseware. Looking back, the following experiences from the digitalisation of object-based courses can be noted:

Pro online format:

Students benefit above all from the possibility to work on assignments at any time. This is a huge advantage for students with child(ren) or relatives in need of care, for example. Students also see an improvement in terms of combining their studies with a part-time job. The online format enables students to easily catch up on missed courses, which is hardly possible with a face-to-face course. The two-hour course focuses primarily on identifying as many species as possible using the specimen. Students often attend the supporting lecture separately from the tutorial. Both a close link between theory and practice and references to additional (online) sources directly in the Courseware can encourage interested students to engage in independent, in-depth study (see Fig. 9).

Within the small groups working on plant identification in breakout rooms, it is possible to work at an individual pace. The automated assessment of plant family, genus and species, as well as the help of teachers, allow students to work through the course content at their own pace. Unfinished tasks can easily be completed before the next week of the course and all of the examples remain available after the course.

From a teaching perspective, the new format also uncovered problems hardly noticeable in a face-to-face course with up to 40 students per group. For example, false entries can be commented on directly and students can be given a hint as to where they ‘took a wrong turn’ in the determination key. In the classroom, generally only students who dare to ask a question will get their answer.

Contra online format:

The three-dimensionality of the objects and qualities such as smell and feel cannot, of course, be conveyed using images. Spatial imagination is often a prerequisite when it comes to recognising how individual organs of the flower are positioned in relation to each other. In order to teach adequately the crucial skills for botany work, additional information on the plants’ physicality is required.

The exam results allow us to compare the skills acquired in the analogue format, and in the digital format of the course. This is possible because the examination format remained in presence and not changed to an online examination. Students also had to take a two-hour written exam at the end of the online semesters, in which one hour was set aside for the identification of two unknown species. The results of over 300 students did not show any poorer results in terms of grades. One of the reasons given by students for the slightly higher rate of failed main examinations was that they focussed on other examinations or planned to take the examination first and then prepare for the exam at a later date.

Conclusions

The unexpected switch to online formats in 2020 required both teachers and students to improvise – and to keep calm. The digital tools did not necessarily bring improvement on traditional teaching concepts, yet a hybrid version of the course might be relevant in the future – combining the advantages of the online format with those of working in person on the object.

This article is a shortened and translated version of a text written for Objektfreitag, available here.

Blume, J., Krämer, C., Link, S., Schulz, S., Will, M., Uphoff, I., Benz, A., Biedermann, B., Breuer, E., Hollwedel, C. (2025). Lernen mit Objekten. Forum Universitätssammlungen. , Band 1, https://doi.org/10.18452/34757

Maria Will

Germany

Dr Maria Will is a lecturer at the Institute of Biology and Environmental Sciences at the Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg. After studying biology in Jena and Leipzig, she completed her doctorate in Mainz and completed a scientific voluntary service. In addition to teaching botany, she is involved in the certificate programme Custodial Practice at University Collections and deals with the indexing of collections.