Give teachers an object budget

Room for advancing insight

Fresco Sam-Sin

22 April, 2024

This article is originally written in Dutch and automatically translated by DeepL AI.

In many educational contexts there are earmarked budgets for continuing education, conferences, budgets for books, travel reimbursement, allowances to buy a bicycle. Moor, but as a teacher who teaches with objects – not (just) for fun, but as an indispensable ingredient – something is missing: an object budget. There must be one!

Until a few years ago, my entire adult life was dominated by Leiden University: I studied there, did odd jobs as a student assistant, wrote textbooks and worked there as a subject teacher and language and culture instructor. Throughout that time, one thing always puzzled me: why is education moving so slowly along with advancing insights from educational science? Surely a university is not only there to produce knowledge, but also to use it to move forward?

No pressure, no obligation

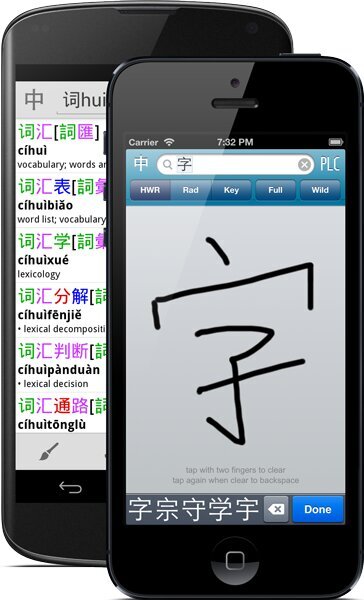

I was trained as a sinologist. Very early in my studies (around 2002), all kinds of digital gadgets began to emerge that made paper cabinets full of dictionaries obsolete (except that they are interesting objects). Not much later, dictionary websites and smartphones full of dictionary apps followed. In short, there were suddenly numerous opportunities to simply have the fifty thousand characters in your pocket.

The teachers lagged behind in this. First it was because young people were stupidly often ahead of the game, then it was more stubbornness and nostalgia. There was no didactic guidance or pressure that would win them over to keep paper dictionaries out of college and go digital with students. And that is not without consequences.

I understood. Moving along sometimes hurts a little, but it is a responsibility that a self-serious education must bear. Nostalgia has no place there; especially when ignoring new insights introduces new errors: with handwriting recognition on a dictionary app like Pleco, for example, it no longer matters what stroke order you write a character in. The bar order in Chinese has strict rules. If you don't know the bar order, you will never be able to read cat calls or calligraphy in quick script.

I see two problems here: (1) not only do teachers get no guidance in the form of customized in-service or continuing education; but also (2) there is no pressure or obligation involved in adapting methods and tools. The same goes for objects in education: we know that it works, that it is an essential addition to accommodate different learning styles and generate more insights that can refute or confirm text. Leiden University has no teacher training for object-based teaching and learning and so heritage collections remain the go to for teachers who want to expose their students to objects, and even that is not mandatory. And, to make it complete, then students often cannot even feel, smell, and move around the objects.

Out of step with the material turn

It really worries me: many language and culture students are not given the opportunity to get a feel for material culture during their studies. And that is completely out of step with the material turn, in which there is a broad-based realization within the humanities that an object is much more than an illustration to a text. It will often be humanities students whose future will be a decisive voice in dealing with our heritage: what do we have too much of? What objects are unjustly languishing? Are there object biographies that tell more fiction than fact? What objects have outdated stories? Or, and this is now under a magnifying glass, what to do with heritage that is still in the Netherlands, but has ended up here in the wrong way. And, no less important, how should we display objects physically and digitally, to allow people who are not allowed to touch or visit an object to have such a meaningful encounter?

It is objects themselves that contain a great deal of information to make considered decisions about an object's story, in addition to the archival documentation and history contained in sources. If we don't teach students to see that, then heritage objects are going to have a very unscientific time with us. Let me make my concerns vivid (for lack of other sensory opportunities) with a few examples, asking the reader to see them in a larger context.

Example:wasuma

The Surinamese washboard (wasuma) in the photo was photographed upside down at the World Museum. Why we don't know. Nor does it say so. For Surinamese seniors (and also for Dutch seniors) this is a nostalgic object. Those will turn it over in their minds and place it in a washbasin in their minds. Some scholars may recognize him from lithographs or photographs. With them, a light will also come on that something is not right about the position of the washboard. They are such "ordinary" objects that photographing them upside down seems harmless. I look at it differently.

Because, what if this generation of seniors is no longer around and, as a web visitor, you don't have anyone standing next to you to tell you, "that thing is upside down," isn't a lot of meaning lost in such a photo? Were you allowed to hold the wasuma, you would immediately understand why this object does not belong with its legs in the air. Would you be allowed to put it in a washbasin, then you also immediately know why the wasuma has the shape it has. The chances of getting your hands on one from the World Museum are slim, but I just looked: you can buy one online anywhere. You can own one yourself. Buy blue soap and dry a corncob and you can experience what it was like. But then ask for budget from your training and invite a Surinamese senior to do it for you.

Qing Coins

I collect coins of the Qing. The founders of the Qing emerged around 1600, to seize power in Beijing in 1644. Linguistically and culturally, their ruling house was related to Mongols and to Turks. Since money is historically one of the most important statements of power, their coins should also convey that there had been a changing of the guard in Beijing. On the other hand, the coins couldn't be too different either. Otherwise people would not trust them and the economy would be jeopardized.

Strategy of the Manchus was to keep the shape (round with a square hole) and the production process (casting instead of minting) unadapted and also keep the obverse of each coin Chinese (a government title followed by tongbao 'circulating treasure'). This had been going on for several centuries before Christ, and changing it would be a risk. On the reverse, however, Manchu, a script that came to Manchus via ancient Turkic and Mongolian, suddenly appeared. People would see (because text lived in an illiterate world) that there was a different script on the coins and could understand it as a change of power. But, if you put all the coins side by side, you will also be able to see that the Manchu script is always very minimally different from each other for each issue. That was also a strategy on the Chinese obverse of the coin, because that's how you prevent large-scale counterfeiting. But, that Manchurian script, counterfeiters had not yet mastered that.

Coins tell a lot of stories and actually you have to be able to play with them with students in order to tell not only the stories of the coins, but also of the society within which they circulated. At the World Museum, I once attended a workshop with Qing coins. We had to wear latex gloves (which we know doesn't protect the coins) and were not supposed to hold it by your nose, as the moisture can encourage oxidation. A lot of the coins were obviously fake. You know that when you've passed enough of them through your hands. Also, the coins worth more than ten euros could be counted on one hand. Most you buy online for less than a euro and then you have a real one. And not only that, then you can compare them, put them in rows, make rubbings with them and so on.

Every student sitting in the pews at lectures like Chinese history, Manchu, world history, identity, numismatics, archaeology would benefit from being engaged with a group of these coins. In a hands-on way, you see confirmed in coins what I had already underlined during lectures: Manchus were able to found one of the greatest empires ever with a small minority because they could make ideology and pragmatism into a good marriage. Well, if coins are so cheap, what are we waiting for?

Space for advancing understanding

It need not be expensive or complicated to introduce objects into the lecture hall that help students engage with materiality in addition to text. Both have something to say to each other, and sometimes one is more right than the other. The method of object-based teaching has its merits. And budgets for things that contribute to teacher professionalization have been around for a long time, so let's not wait to give room for advancing insight. Give teachers budgets to purchase objects for their lectures. And not in a few years, no now. Because, really, in these times where there is a lot of tension around collections, students need to know the collections better.