Finding Manchus in the Wereldmuseum

Fresco Sam-Sin

22 April, 2024

In the heart of the city of Leiden, I took my students to see real Manchu objects. Manchus were the rulers of one of the biggest land empires in world history (1616-1912), with China making up the biggest part of their realm. These language students were in for a new experience. Let me tell you about it in this piece.

Where are we?

We are standing with my students in the depot of Museum Volkenkunde, in the heart of the city of Leiden. The visit is part of my Manchu language and culture course. Manchus were the rulers of one of the biggest land empires in world history (1616-1912), with China making up the biggest part of their realm. Manchus are culturally and linguistically closely related to Mongolic and Turkic peoples. One of the misunderstandings about the Manchus is that they - as if sprinkled with fairy dust - became Chinese with the passing of the Great Wall in 1644. Debunking this idea is one of my biggest goals in my teaching.

Before me on the table, you see two bows and two arrows. Outside of this image there were more bows, arrows, and other archery equipment. The museum curator is on site, and allows me to touch the objects, with gloves on. It is my task to make sure that my students can experience materiality without manipulating the object. I guide their slow watching, while I carefully choose my words, making sure that I address all the senses other than their sight.

Preparations

Two months in advance I made sure that the museum curator reserved time in her agenda to welcome us; this would also give her enough time to have the objects sent over from the depots outside of Leiden. Also, the preparation time allowed me to build up momentum with my students. Indeed, when the day arrived, the students were excited. Understandably so, since, in their text-oriented studies, they hardly come across real objects. That was about to change.

The objects that I selected all shared a common theme: Manchu archery. In history, archery is one of the most important pillars of Manchu identity. Hence, objects related to this are a must see in my course. In fact, the waning skills in Manchu archery throughout the centuries of Manchu rule was one of the biggest frustrations of the court in Beijing. The central position of archery becomes clear when you look at the Manchu verb Manjurambi, which we can translate as 'to Manchu'. The verb has two meanings (1) 'to speak Manchu' and, surprisingly, (2) 'shooting arrows whilst riding a horse'. Reading this lemma is a staple in the third week of my beginners course, and thus, before entering the premises, the students are aware of the status of archery within Manchu governance.

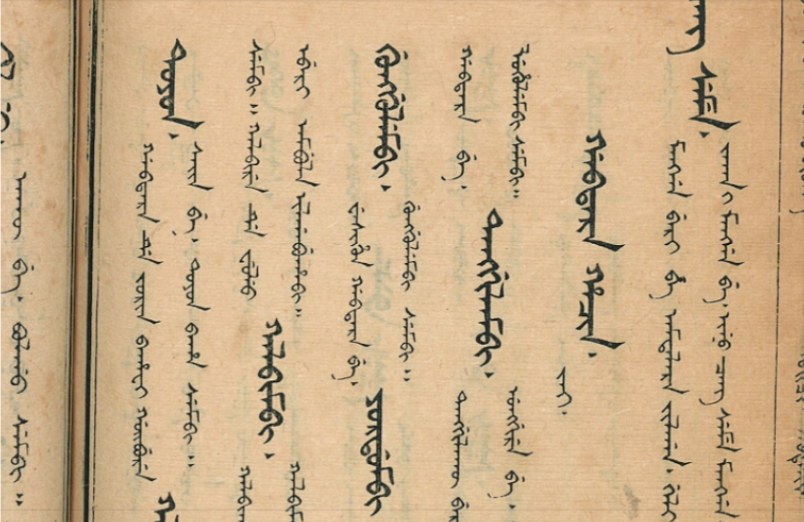

Before class, the students already read entries related to all the sounds that arrows make, underscoring the richness in archery vocabulary. I use the sacred Mirror dictionary, commissioned by the Kangxi emperor (r. 1661 - 1722, here). Apart from the philological preparations, I also ask students to explore a digital table of Manchu arms and armor, put together by myself and Peter Dekker who is the absolute specialist in Manchu arms and armor (here I use questions, and here we hear the specialist).

IMAGE 1: Sounds of an arrow. The linguistic term for this are ideophones.

IMAGE 2: What one helmet can tell us

Goals

In the picture, you see a curious curator and two students. I ask my students to focus on the bows. I have three learning goals in the back of my mind, and all that we learn on the side during this session is a win. The goals:

(a) First, after this workshop, my students understand that material sources are able to confirm our textual knowledge of history; and (b) students understand that there is a lot of information that we cannot get from textual sources. Learning that an object has its own stories to tell; and (c) the students realize that material sources can go against texts, or at least leads to questioning the value of written sources.

Have a look at what I did. Did I reach my learning goals? Also, think about how this could be relevant in your own teaching. Make sure to leave questions and comments at the end.

Confirm the written sources

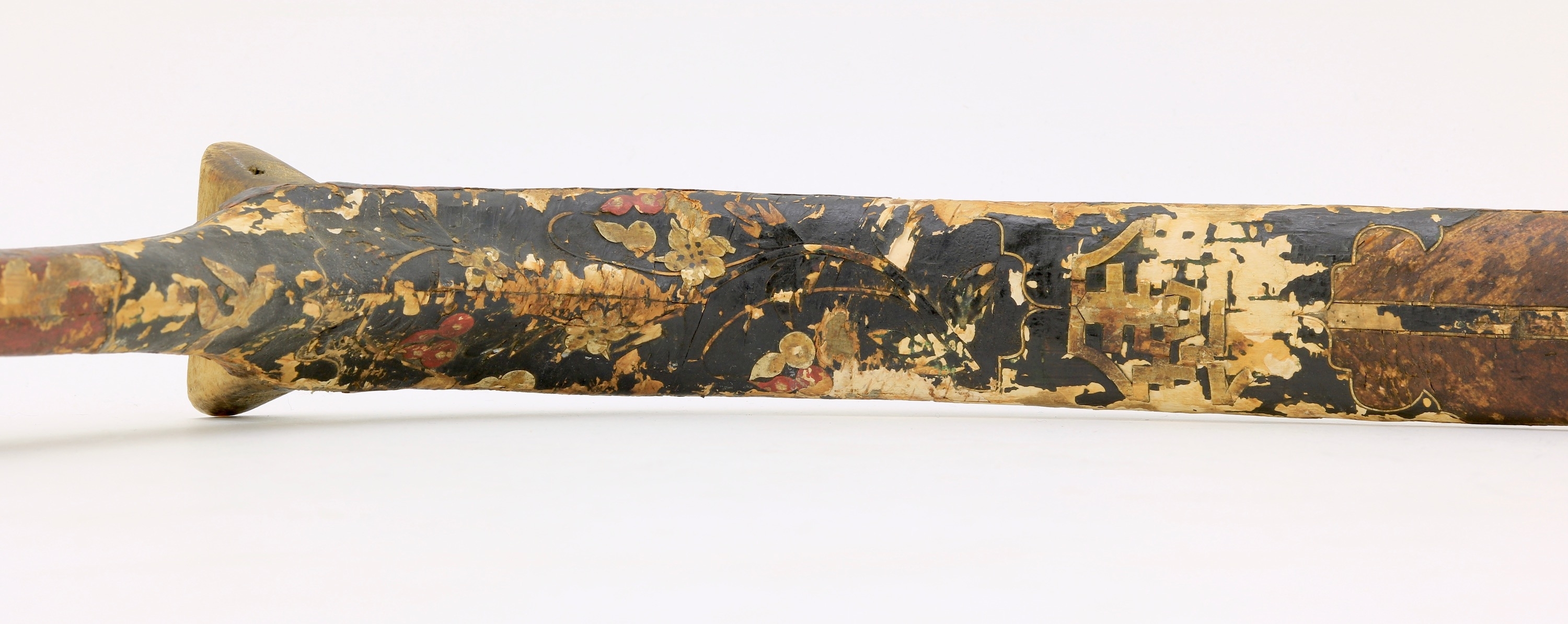

I ask students to compare the two specific bows. One is at the back of the table, the other one is not visible in the picture (link), but to give you an idea, image 3 and 4 show some comparable motifs. I ask them to find elements that are different.

This seems like an easy question, but language-oriented students need time to get into the object-modus. One student said: "there is a big difference in decoration. The one in the back has a more natural motif, the other one has floral and more flamboyant". This observation helped us to address our first learning goal. The Manchus conquered China as a very small group, a semi-nomadic people that lived from hunting and fishing. Complex, flamboyant decorations was something that the rulers detested. They took it as a distraction of 'the Manchu way'. You saw this in other objects as well: travel cutlery sets always consisted of not only chopsticks, but also of a knife, since a real Manchu - this was the policy - would not allow others to cut their meat. It was the ruler's hope that Manchus would not forget their humble beginnings, their language and their skills in horseback archery. Floral designs were something for the Han, they liked to emphasize.

But, as this student knew, and also shared with the group, Manchus, in many ways, absorbed the Hochkultur of the Chinese, especially after the times of the great wars. The bows are an example of this transition: while the one bow is very natural, and very simple in decoration, the bow with the floral design seems to focus more on presentation, and not so much on effectiveness. Indeed, by the end of the empire only few Manchus knew how to manjurambi, 'speak Manchu' and 'shoot from horseback'

IMAGE 3: Qing bow

IMAGE 4: Qing bow

IMAGE 5: Qing bow in collection Volkenkunde.

IMAGE 6: Qing bow in collection Volkenkunde.

Unwritten stories

Objects tell their own stories, opening directions that we did not think about yet. To underscore this, I asked the students: "looking at their usability, what is the most important difference between the two bows in front of me?" (both visible in the photo). One student was quick: "only one has a string." "So the one without a string only needs a string from one end to the other, and that's it?" The class confirmed.

I continued: "Only one side of the bow without the string is decorated with the stripes. Are you telling me that the decorated side is directed towards the archer?" Only by asking this, the students realized that before a bow can be strung, it has to be stretched in the other direction. My question unleashed a whole series of questions about the materiality of this bow and the other bows on the table, and therewith also opening discussions about the availability of resources, and human labor and craftsmanship.

For example, the outside of a bow is made out of a complete watterbuffalow's horn. Where did these animals come from, are there records of special breeding places. How did one glue a bow together? The pressure when stretching, stringing and shooting is exceptional. Only one glue would do: fish bladder glue. The green parts where arrows make contact with the bow, what are those? The last observation was what I needed to move towards this workshop's final goal.

IMAGE 7: Deconstructed Qing bow

Questioning written sources

As said, the sacred Manchu Mirror dictionary dedicates a lot of space to the explanation of words that have to do with archery. One is hasutai. Hasutai means 'left handed'. The lemma is very clear about this: 'a good archer is both right and left-handed.' After I presented this piece of information to the students, I asked them to confirm or question this lemma. How normal was it to shoot with both hands? Was it part of the training, a compulsory skill, needed to pass the exam?

Going back to the green piece on the bow. The green elements are on both sides of a piece of cork. The green is rayfish skin. Rayfish skin is the strongest leather that you will find. You want it to be strong, because in war and during training, countless arrows will have to run via this part of the bow. Of course when shooting, the skin will show wear. Now, look at the rayfish skin in the image, and also be mindful of the unstretched state of the bow. How did this soldier shoot his arrows? In any case, the bow shows that the arrows only passed along one side. And, this bow is not an exception. On the contrary, all bows show right handed shooting. The Mirror is, as imperially commissioned works often do, portraying a big wishful thinking. From the bows we know, that mixed-handedness was a rarity.

By this time the questions kept on coming, giving me enough ideas for the weeks to come. One student asked: "Was there a time in Chinese history where people were forbidden to use their left hand? And, if so, is this bow an example of this prohibition?" I did not know what to answer, and in that moment I knew that this workshop was a success.

IMAGE 7: Qing bow

IMAGE 8: Qing bow